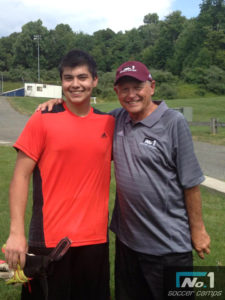

Dr. Joe Machnik, No. 1 Soccer Camps Founder and former Assistant Coach for the 1990 US Men’s Team, recently shared some of his memories of the 1990 World Cup. Les Carpenter’s An Oral History of USA at Italia ’90: the World Cup that Changed US Soccer captures the excitement and the drama surrounding a team of unknown US players tasked with representing their country in the World Cup for the first time 40 years.

An oral history of USA at ITALIA’90: The world cup that changed us soccer

by Les Carpenter

On 10 June 1990, a bunch of unknowns stepped on to the pitch in Florence – and launched modern soccer in the US. America’s pioneers recall an Italian adventure

Steve Trittschuh recognized the figure slowly approaching the American locker room beneath Rome’s Stadio Olimpico. This was June of 1990, the middle of the World Cup, and everyone knew the silhouette of Italy’s best player, Roberto Baggio, with bushy curls piled on his head. But why was Baggio here? Why was he outside the locker room of the team Italy had just beaten 1-0? And why was he clutching what appeared to be … his game shorts?

“Hey,” Baggio said to Trittschuh, changing just inside the door.

“Hey,” Trittschuh replied.

An awkward silence filled the space between them until Trittschuh realized what was happening. Baggio, perhaps the greatest player of his time, was asking a 25-year-old defender from Granite City, Illinois, to trade pants.

“I had Baggio’s shorts forever, man,” Trittschuh said one recent morning as he prepared to coach his Colorado Springs Switchbacks of the United Soccer League. “It was the coolest thing.”

Long before Major League Soccer, regular World Cups for America and Saturday games on network TV, there was a team that launched modern soccer in the United States. It was a group of unknowns, many of them fresh from college, who had been handed an impossible task: become the first American team in 40 years to go to the World Cup.

For nine months in 1989, the US players battled to seize one of the two Confederation of North, Central America and Caribbean Association Football (Concacaf), spots in the 1990 World Cup. Eventually, they did, with a miracle goal scored on a tiny island off the coast of Venezuela. Then 25 years ago this week they stepped on an Italian field and launched a movement.

This is the story of America’s soccer pioneers who walked into a world they never could have imagined.

1. From the Stone Age

Bob Gansler (Head coach of the US men’s soccer team 1989-91): We didn’t think about the difficulties of the venture. That’s just where soccer was at the time. There was no professional soccer at the time.

John Polis (Director of communications, US Soccer Federation 1988-93): Soccer in the United States was the Stone Age compared to now.

Gansler: We tried to put together a squad of talented people who could do things together, and could go through adversity as well as perform. There was no way outside of Concacaf where we would be the favorite. We wanted guys with gonads who could handle the situation.

Paul Krumpe (midfielder): Even with guys who had professional experience, our experience was so minuscule. It was imposing for us against everyone we went up against.

Bruce Murray (forward): There were a lot of indoor league guys like Ricky Davis, and the sports writers were saying these need to be the players in the World Cup, these are professional players, grizzled players, but Bob Gansler is like: “They haven’t played outdoors and [don’t have] the fitness levels.” He stuck with the college guys. A lot of people criticized him for it.

Polis: In 1988, Fifa had announced the 1994 World Cup was coming to the United States.

Murray: Can you imagine what an embarrassment it would be to not have qualified for the previous World Cup and be awarded the World Cup? There was even some talk about taking the World Cup away.

Gansler: I said: “Let’s get together a team not just for 1990 but for the 1990s.”

Murray: We were the guinea pigs.

Steve Trittschuh (defender): There was a group of us – like 13-14 guys – and we started together at the end of 1986 and beginning of 1987. It was a good group. We all had to learn the game. Gansler taught us.

Polis: The task was enormous. There was this big, huge mental block hanging over this team.

Gansler: We played catch-up but we were running fast.

Polis: Gansler was a terrific guy who was in a tough situation. It was a little bit like Herb Brooks with the US hockey team. He wasn’t blustery. He had a businesslike manner. He was coaching a bunch of kids trying to get to the World Series. That’s what it was like – taking a bunch of 22-year-olds to the World Series.

Peter Vermes (forward): I always admired the job he did at that time. It was like the movie Miracle. He had to take college players and turn them into men playing at the highest level in a short time.

John Harkes (midfielder): I think Bob Gansler had a keen eye to not just observe the ability of the players but to see the desire of the team you are putting together. It’s hard.

Mike Windischmann (defender and captain): I remember one time we were in East Germany, and we were training a lot. So some of the guys said: “Hey, Mike go talk to Bob and ask him if he could cut down the practices a little bit.” So I got to Bob Gansler’s room, and I say: “Some of the guys are a little concerned, you know, with training.” And he was like: “Oh, all right.” Basically, it was like: “Tell them to go to hell. We’re still practicing.” I go back and everybody’s huddled up. “What did he say?” He said: “Go to hell. We got practice next morning.”

Joe Machnik (assistant coach US men’s team 1989-90): I would say Bob was authoritative. He was a serious-minded coach who believed the players had to behave a certain way off the field.

Murray: We had a lot less … professionalism. I guess that would be the word. But we got it done.

Vermes: It was amazing if you look at the resources [Gansler] had to achieve what he needed to. Back in those days we had a $5 per diem.

Gansler: When we qualified for the World Cup, our federation president, Werner Fricker, put up his Philadelphia construction company as collateral to have a loan that got us some more money.

Krumpe: The big benefit to us [in qualifying] was Mexico using ineligible players [in 1988 Olympic qualifying] and not being part of the Concacaf. There was a huge opening without Mexico. Everyone felt the same way. It was the time to qualify.

Gansler: I was glad we were getting covered by more journalists, but they had never covered soccer before. They didn’t know much about soccer or Concacaf. They pulled out the atlas and said: “You’re playing against Guatemala or you’re playing against El Salvador, and should be able to beat them anyway.”

John Stollmeyer (midfielder): I was always surprised that it was close for us in getting through qualifying. The older I get, I realize it’s difficult. It got to the end of those last several games and it was a battle.

Gansler: I knew it was going to be a long road. Early on, after a game against Costa Rica, I said: “More than likely it’s going to come down to the last game of qualifying [against Trinidad & Tobago].”

Murray: It wouldn’t have come down to Trinidad if we had won the El Salvador match right before that. We blew it.

Trittschuh: That was tough. El Salvador was not in [the running for the World Cup] at the time and they sent a really young team and we just couldn’t score (a 0-0 tie). The way things happened is a great story but we could have made it a lot easier on ourselves.

2. The shot heard round the world

Costa Rica had already grabbed one Concacaf qualifying spot. The US and Trinidad & Tobago were tied for the second with nine points. Since Trinidad had a two-goal differential over the Americans, the US could not make the World Cup with a tie. It needed to win or face the shame of hosting a World Cup in four years without having been to one in more than four decades. The match, scheduled for the afternoon of 19 November 1989, in Trinidad’s national stadium, became the biggest American soccer history to that point.

Gansler: The federation got us a camp in Cocoa Beach, Florida, for 10 days, and they even flew in Bermuda to play us to prepare, because they played the same way as Trinidad – an athletic team who was quick.

Machnik: We struggled against Bermuda, so the media around us was very skeptical. They were writing that we can’t win.

Polis: There was angst among the press at the time around the team. Could [the US] do this on the road? There were people in the press corps who thought we were going to get thumped.

Trittschuh: I knew we could play against Trinidad. but in the back of our minds we wondered what was going to happen to US soccer if we didn’t win – and then what was going to happen to us?

Gansler: I remember at the airport, as you walked off the plane, you walked into a sea of red. All of Port of Spain was wearing red that day.

Polis: There were 10,000-15,000 people screaming: “No way, USA! No way, USA!” People were banging on the side of the bus.

Vermes: There were even people on the roof of the airport. It was crazy.

Trittschuh: It was 10 o’clock at night. As we were driving down the highway there was a lot of people lining the road all the way to the hotel.

Murray: They had declared a national holiday the day after the game to celebrate going to the World Cup.

Krumpe: They were so convinced they were qualifying for the World Cup, they got all their artists to record World Cup songs, and were playing them on the radio.

Polis: On the morning of the match, a lot of us in the delegation were invited to breakfast at the ambassador’s residence. It was a beautiful house that looked down on the stadium and at the water. The stadium was already filled at 11am.

Murray: The bus ride into the stadium was at 2mph, and everywhere you looked it was red. I’ve played before bigger crowds, but it was a very intimidating atmosphere. Everybody was dressed in red.

Vermes: You could feel the tension of the occasion. It was us against the world.

Murray: There was a park next to the stadium with a Jumbotron, and there were 100,000 people watching the game, and the stadium holds 35,000, but there were people climbing up the walls.

Stollmeyer: There was only a rail around the field and people were actually sitting on the track.

Murray: I don’t think there was a lot of belief in that locker room. You could ask any player. You were young, you weren’t sure you were getting another contract [with the national team]. You had to win to survive. I was getting married a week later, and I was like: how am I going to take care of kids?

Gansler: I told them before the match: “[Trinidad] will take chances, that’s the opportunity we can have. That opportunity is going to be there.”

Vermes: I remember walking out of the tunnel before the game. You could see the terror in the [Trinidad players’] eyes, because of all the pressure to go to the World Cup that had been placed on them.

Play by play: Ramos…putting it in…to Caligiuri…beats the first man, a left-footed shot…Paul Caligiuri has scored a goal and the US leads 1-0!

Gansler: Paul just let it fly.

Windischmann: He just flicked it over and just hit it. It was surreal, like in slow motion, the ball continuing and just dropping in.

Machnik: The moment Caligiuri hit it, I jumped up and yelled: “Trouble!” The sun was in the goalkeeper’s eyes.

Gansler: The goalkeeper did not have an NBA vertical. It had a chance.

Machnik: The ball was in the perfect spot. I think it hit the ground before it hit the net.

Vermes: We were all amazed when the ball went in. It was almost as if: “Holy cow! We got this thing now.”

Murray: When Paul scored his goal, we realized: “You know, we can win this game. We probably can score another one.” There was no belief until Paul scored and then there was belief.

Stollmeyer: During the rest of the game you were wondering: “How much more time were they keeping on the clock to give them a chance?” I kept thinking: “When are they going to blow the whistle?”

Windischmann: Some people just fell down afterward. There was shock when that whistle blew, because we were waiting and waiting for that whistle to blow. It was just a relief when that whistle blew and it was: oh my goodness, we are going to the World Cup! It was unbelievable.

Polis: The celebration in our locker room was tremendous relief. Bob Gansler was in the corner nursing a beer. He said: “Just another game.”

Trittschuh: It was a relief. By the time everybody got back to the hotel, everybody was exhausted. We didn’t even have a party that night. Everyone just sat by the pool.

Murray: For us, [losing] would have been a disaster. All this that you see now [in US soccer] is because of what Paul Caligiuri did in Trinidad & Tobago. It’s as simple as that, if you want to pin it to one specific moment. For example, Nike jumped in with hundreds of millions of dollars to build all these academies, and that never would have happened if Paul hadn’t scored that goal. They should put Paul on a lifetime stipend. Seriously.

3. Three stripes or you’re out

Krumpe: The US Soccer Federation had not been through this since 1950. Nobody knew what you were supposed to do. Do you give bonuses? Do you fly everyone to a training? Everything was new to them.

Trittschuh: After we qualified, we had to sign another contract, because it was the start of another year.

Stollmeyer: They flew us to New York.

Trittschuh: In New York, we all got into a room and they all presented what [the contract] was going to be.

Krumpe: Then they brought us into a room one-by-one.

Stollmeyer: They gave us the contracts and we either signed them or we left. There wasn’t any negotiation. They said: “This is it.”

Krumpe: It was minimal. It was less than $50,000 a year.

Trittschuh: I want to say it was between $40,000 and $50,000.

Windischmann: It was $40,000, I definitely remember.

Stollmeyer: It floored a lot of us, in terms of: oh my God, look at what we did, and they aren’t going to take care of us?

Krumpe: I have an aerospace engineering degree, and I had a great job with McDonnell Douglas designing the MD-90. It was an unbelievable job. They couldn’t believe I was walking away from it to play soccer.

Murray: I had just bought a house in Bethesda [Maryland] right by Suburban Hospital on Garfield Street.

Stollmeyer: I got married in February of 89. My wife was still in med school and I had car payments.

Trittschuh: A few of the guys thought they were being a little bit bulldozed by the federation.

Stollmeyer: The problem with the whole thing was that we couldn’t have individual shoe contracts because the federation had a deal with Adidas. There was no means to make more money.

Polis: The federation was short on funds at the time. I don’t think they were getting much of anything. They got a deal with Adidas and I don’t think they got much more than product.

Windischmann: We were approached about signing Puma contracts.

Krumpe: There were 10 of us under contract to Puma at the time, and we had to give that up to go to the World Cup.

Windischmann: Puma gave us, I think, $10,000. They gave us boots and gave us equipment. At the time Adidas wasn’t giving us stuff like that, so it’s kind of hard to say: ‘No”.

Polis: There was one guy at Puma who was pouring gasoline on the flames. I remember one day when a bunch of them walked out to practices with Puma gear on, and Gansler said: “Go change.”

Windischmann: I think it was in San Diego, and we put the Puma boots on only to have people tell you: “You can’t wear those.”

Stollmeyer: Here we were, at the best time of our lives, and we were fighting over how much we were getting paid.

Trittschuh: We all stuck together as a group for a while until everybody finally went their own way. I wanted to play in the World Cup. What else were we going to do?

Polis: It’s got to be hard when at age 20 you’re getting told: “You’re getting screwed by the federation.”

Stollmeyer: Two guys I remember held out. They showed up to camp without contracts.

Gansler: I finally said to them: “This isn’t the German federation or the Brazil federation or Argentina. This is us.”

Trittschuh: We all stuck together as a group for a while, until everybody finally went their own way. I wanted to play in the World Cup. What else were we going to do?

Krumpe: As a 32-year-old without an outdoor pro league to play in, there was no chance but to say yes to the contract. There were sacrifices to be made, including wearing Adidas shoes.

4. ‘It was like a prison’

The US was faced with a daunting task in its first World Cup in 40 years. At the draw, actress Sophia Loren picked the ball that placed the Americans in a loaded Group A with rugged, experienced, Czechoslovakia; the host Italy – one of the world’s finest teams – and Austria, then a rising soccer force in Europe. The Czechoslovakia and Austria matches were to be played in Florence. The US would face Italy in Rome.

Gansler: To go to downtown Rome and try and prepare with all the spotlights and media and all that … I thought it wouldn’t serve us. I thought it would be better for a group of young guys that, rather than spending extended time with the media, we should be somewhere secluded.

Machnik: There are several theories on whether a team should be sequestered or at a downtown hotel. It had been 40 years since the USA had been to a World Cup, so no one had an idea what we should do. But Bob told the federation that we should be sequestered.

Gansler: We were booked to go to Coverciano, the [soccer] training center of Italy, which is located just outside Florence. That’s what the agreement was. If you look up the official Italian training center you’ll see how nice it is.

Machnik: We were going to share it with [the Italian team]. Then we got put in the same group as them and they didn’t want us training with them anymore.

Gansler: They said: “We have an Olympic training center a little farther away in Terrenia. It’s comparable.” We didn’t have any money to go out there ahead of time and find out it wasn’t comparable.”

Harkes: It looked like barbed wire [on the top of the gate]. Where are we going?

Polis: It was a dormitory-like training facility. It wasn’t in town, it was out in the country a little bit. There were a lot of Italian carabinieri law enforcement guys. We had guards stationed all around the compound. They were well-armed.

Vermes: It was like a prison. Anytime you wanted to go out a guard went with you.

Murray: It was almost like a compound.

Harkes: We pull in, and there’s a track around the field, and that was it. There were these little complexes on the site and that’s where we were staying.

Trittschuh: It was a little bit of a letdown. It didn’t feel like we were at the World Cup. It was a prison camp.

Machnik: Lets just say it was Sparta compared to Athens.

Stollmeyer: The problem was: we were watching on TV all these big teams coming out of these posh hotels. Why aren’t we living like that?

Gansler: They assured us it was comparable [to Coverciano]. Where we thought we had a four-star complex – we went there and found that. I felt bad and wanted better. I could have stood there and pitched a fit, but those were the cards we were dealt.

Machnik: After the World Cup they brought all the World Cup coaches back to Coverciano for a seminar with the coaches from Serie A. It’s a nice place, you can imagine, the Italian team stayed there during World Cup. Our players would have loved it.

Gansler: I didn’t go out there before, our coaches didn’t go out there before. We couldn’t afford the plane trip to check it out, and we couldn’t afford the time away from the team. Maybe our shortcoming was that we were too trusting when the Italians told us it was comparable

Trittschuh: We trained twice a day. When we started they had a cafeteria and the food wasn’t good, so eventually they found us an Italian restaurant outside, just so we had one good meal a day.

Murray: We were away from our families, had very little time with our families, and I think that was a big mistake. Now they have players stay at the Westin or whatever. The team will take over the whole hotel in the World Cup. They don’t seclude them completely from their family. My family, we had 50 people over there – it was like a big celebration, but I could never get to see them.

Krumpe: There was a sponsor who paid for anyone who was married and their spouse and family to travel to Italy. That was a nice touch.

Polis: When we were there the US was thought of as neophytes, and how did we get there? They said if we got there then Concacaf must be so weak. That was the overriding view.

Gansler: Czechoslovakia had a lot of internal crisis going into that World Cup. They were in turmoil. I thought watching their films through qualifying that this was the one game to get a result. Maybe I’m conservative in these matters but a result would be a tie.

Machnik: We thought our best chance was against Czechoslovakia. Only later on, when I was at the coaching seminar in Italy and I talked to their coach, did I find out how bad their internal issues were.

Stollmeyer: I remember our coaches telling us the Czech game was the one where we had a chance to get a result. I thought: “Really? I don’t remember playing an eastern bloc team that wasn’t hard and couldn’t run our asses off.”

Murray: That first game we weren’t really prepared, I don’t think. I remember Joe Machnik telling us that physically we would be imposing, and we were lining up in the tunnel to come out, and I’m right next to Tomas Skuhravy, and he’s, like, 6ft 5in, and the two center-backs are 6ft 4in, and I’m thinking: “What the hell?”

Gansler: We had opening-game jitters. We gave up a goal just before half – it would have been easier to go into half down just 1-0. To be down 2-0 was much worse. We were a young team and we self-destructed. Eric Wynalda got tossed out of the game.

Murray: We just got smashed.

Windischmann: We got beat in the air. But you have to remember both of those teams went to at least the quarter-finals – Czechoslovakia and Italy – so we weren’t playing against just teams that so happened to qualify. So we had a tall order.

Harkes: There were a lot of deep thoughts among the players, among ourselves: “Are we really up for this thing?”

Murray: So now you can imagine going into the second game against Italy in Rome … The Italian paper La Gazzetta dello Sport was like: “Can the Italians score 12? “You have to remember the Italians were the best team in the world cup according to 90% of the people over there. Their line-up was ridiculous.

Polis: This German journalist asked: “Mr Gansler, what would be an acceptable number of goals to lose by? Five goals? Six goals?”

Stollmeyer: After the Czech game, team morale was not great. Practices were brutal. Changes were coming on the field. There were guys coming out to practice in screw-ins and it was really hard play.

Trittschuh: There was a lot of frustration. There were guys who weren’t starting and thought they should have been starting. We had three straight weeks in that place and guys were getting sick of each other.

Stollmeyer: We had to say: “Hey, we’re teammates here.”

Windischmann: I think maybe it’s that mental aspect that gets to you when you are doing that same thing over and over again. We hardly had any television, [ate] regimented meals. Then we started going back to our rooms getting on each other’s case because you’re there so long.

Vermes: We had a big fight. It was Murray and [Eric] Eichmann. It was a melee, everybody was basically in the goal throwing punches.

Murray: I felt that Eric had targeted me in training, and if he made me look bad it would help his cause to get into the next game. So a couple of late hits, and that was it, and the gloves were off. I have no problem today with Eric, but it does show the competitive atmosphere within the group.

Vermes: It was letting steam off.

Harkes: I would have to think Gansler would look at that and think: “This is good.”

5. Respect, finally

Murray: On the way to Rome we had helicopters flying beside the bus, literally down low, like five feet off the ground, and another sweeping across the road, like, maybe five feet off the ground. There was some threat, apparently, from some terror group that they were going to do something, so that was a concern.

Stollmeyer: There were one or two (police) cars ahead of us, and two or three in back of us and one on the side, and a helicopter above us. The bus never stopped. We would come up to a toll plaza and it would be cleared and the bus would never stop going through the tollbooth.

Machnik: In Rome, the bus would come to a major intersection. The bus would stop and the (police) would get out of the car with their guns and look around and then wave us on.

Stollmeyer: They all had Uzis hanging out of the cars.

Gansler: When we drove over to Rome, there were people on the side of the road. They figured out it was our bus and they’d come to stand by the road and hold up 10 fingers. They weren’t giving an Italian greeting. It was them saying: “We are going to beat you by 10.”

Polis: People were coming out of their houses holding up 10 fingers.

Machnik: They were just standing there holding up 10 fingers!

Gansler: On the day of the match, I remember Joe Machnik coming to me saying: [the players] want to have a meeting. I said: “Why not?” Those are meetings where leaders stand up and they are accountable.

Stollmeyer: It was in a ballroom of the hotel in Rome. It had a stage up front and 30 or 40 theatre seats. The captains sat up on the stage, everyone else was in the seats.

Vermes: I remember a lot of guys talked.

Stollmeyer: Guys were complaining, and I had just had it with the bullshit. I basically called anybody out who was whining and moping. I said: “We are here for us, and let’s just go out there and play.” Brian Bliss later told me: “You set the record for F-bombs in two minutes.” John Doyle said: “Nothing else needs to be said.”

Gansler: So those guys did have gonads after all!

Vermes: We got to the stadium quite a few hours before the game. There were only, like, 500 people in the stadium and the stadium was so loud already.

Stollmeyer: The field was just like a putting green – it was spectacular. There was a fog smoke in there, flags were waving, people singing, you couldn’t hear a guy five yards away.

Murray: When I walked out of the stadium tunnel (at the start) I was standing next to Paolo Maldini, the famous AC Milan player. I look over to my right and Franco Harris and Tom Landry were sitting in the front row. I went like: “What the hell is this?” You couldn’t miss them. Tom Landry with his fedora. Franco Harris with his beard. (Franco) kind of smiled at me – a very surreal scene.

Gansler: I thought if we could control the ball against Italy their Adam’s apples would be – should we say – upwards, because of the expectations that they would beat us by 10 goals. That’s exactly what happened.

Murray: Bob Gansler said: “This is our gameplan: we are going to defend two blocks of four, and we’re going to hit them on the counter-attack, and you need to hold the ball more.” And we did. Everything came off exactly as planned.

Harkes: We had a sequence where we had 23 consecutive passes without the Italian team touching the ball. In order to do that, on that stage, is pretty remarkable in itself.

Machnik: We could have won that match too.

Murray: The crowd started to turn on their team in the first half because we were just hoarding everything. I was winning my individual battle. And the whole idea was to get it up to me. I would hold it up so we could get some defensive players out. So it actually turned out to be a real battle. I watched that film a thousand times, and it’s the best game I ever played, and not because I scored goals or did anything – but because I held the ball for the team against two of the best defenders in the world.

Trittschuh: We got lucky in that game because they had a penalty kick and they missed the kick.

Murray: I think we had 15 minutes left in the game [losing 1-0] and I got fouled. Free kick from 24 yards out. I sent it over the wall and Italian goalkeeper Walter Zenga dove and knocked it down right in the path of Peter Vermes. From six yards out Peter hits it and it hits both of Zenga’s ankles.

Harkes: Then it hits [Zenga’s] butt. He falls down.

Murray: (The ball) starts spinning on the line. In slow motion you could see the ball spinning.

Vermes: Then it got cleared off the line.

Windischmann: It was like Caligiuri’s goal, slow motion and surreal moments and hoping that ball would go over the line. That would have been nice.

Vermes: I always say one of two things could happen there. I score that goal and I get to play in Italy right after, or I could be where I am today. But I’m happy where I am today.

Gansler: We could have walked out there with a 1-1 tie. Would it have been a true representation of what happened out there? No. It would have been fortunate. They were the better side so we could live with a 1-0 defeat.

Stollmeyer: We knew we were eliminated, but in our minds we knew this is a better representation of who we are and what we can do. I don’t think it was a disappointed atmosphere afterwards. We weren’t disappointed.

Gansler: I remember the first question in the press conference was: “How thankful are you for being so frigging lucky?” I didn’t think that question was proper. [The Italian press] was disappointed and it got under their skin.

Harkes: There was a player that wore No 6 [the same as Harkes] on the Italian national team. I think it was [Riccardo] Ferri. I wanted to change my jersey with him. He was trying to explain that he had promised it to someone else, so he took off his shorts and I looked at him and thought “Well, OK,” and so I took off my shorts. I remember walking down the tunnel in my underwear with his shorts in my hand and I didn’t care … That was kind of odd.

Polis: There was this guy outside our locker room after the match, and he was trying to get in. He was arguing with a security guard. It dawned on me it was Marvin Hagler! I said: “Marvin, can I give you some help?” He said: “Yes, I’d like to go in.” So I took him into the locker room.

Peter Vermes is put under pressure by Italian defenders Giuseppe Bergomi and Riccardo Ferri. Facebook Twitter Pinterest

Peter Vermes is put under pressure by Italian defenders Giuseppe Bergomi and Riccardo Ferri. Photograph: Bob Thomas/Getty Images

Murray: And then there’s a little bit of a commotion – the Italian team comes into our locker room to shake hands. I don’t know who the spokesman was but (he said): “We want you to know that your country should be proud of you.” I’ve never had that happen my entire life. These are superstars: Paolo Maldini, Roberto Baggio, Riccardo Ferri. That was incredible.

Harkes: It was so respectful.

Windischmann: The whole Italian team comes in and they wanted to trade whatever we had, which makes you feel great, you have the Italia team – Baggio – coming in. He wanted to trade jerseys, which was pretty incredible.

Krumpe: I not only exchanged my practice jersey, I exchanged my practice sweats, too.

Windischmann: I got a Baggio jersey!

Vermes: I actually got [Franco] Baresi’s jersey. He was one of the best defenders in the world.

Polis: When we were on our way back [to Tirrenia] people were coming out of their houses again, and this time they were giving thumbs up or clapping over their heads.

Murray: The next day, while we were driving in the bus to training – this is really cool – all these house’s light poles now had Italian and American flags flying together all throughout the town.

6. ‘Something to build on’

Gansler: We thought it we came up with the same kind of performance against Austria that we had against Italy we’d have a result. But every game is different. Where against Italy the onus was totally on them, with the Austrian team the onus was a little on them, but they had the performance they wanted.

Murray: The game against Austria, we’ve got confidence. We lost 2-1 to Austria but we had all kinds of chances. We knew we were done but anyone who says you don’t play for pride – you have to, you’re playing for the United States of America.

Gansler: Their two goals were on counters. That means we were on the throttle.

Harkes: Ever since 1990 we have been representing the United States in the World Cup. So on a bigger scale we did it. Sure, we lost the three games, but it was something to build on.

Machnik: We opened the eyes of the USA to soccer. We helped bring soccer back into the mainstream.

Windischmann: You talk about being pioneers … before 1990 it was very difficult to get tryouts in Europe or anywhere else, so we kind of broke the barrier at the time. I went over to a German league, so now people started to go for tryouts, you know. These days you make a phone call and you get those tryouts. So I think that’s the blazing trail for some of those teams.

Gansler: What I take away is: hey, here’s what we did well, and didn’t do well, and how the game is going to change. We needed to get an MLS – a professional game – because a player’s evolution of his game comes when he practices with good players and plays against them. If you don’t have a league you are at the end.

By 1991Werner Fricker was no longer the president of US soccer. The federation decided it wanted a coach with foreign experience and hired Bora Milutinovic, who had coached Mexico and Costa Rica in World Cups.

Trittschuh: There were a lot of that group in 90 that Milutinovic wanted to get rid of so he blew it up.

Machnik: Bob Gansler’s hard work, and his decision to stick with American kids, was not appreciated. There was pressure that we needed a coach that wasn’t an American coach. I think that was misguided.

Gansler:I thought I would have another chance. We didn’t set the world on fire in 1990 but I had gained a hell of a lot of experience. If Werner Fricker had remained, I would have had a chance but Hank Steinbrecher came along [as secretary general] and they wanted to go a different way.

Harkes: I still think Bob Gansler is completely undervalued in where the game is. Because of him and his belief and his keen eye for heart, for players and the discipline he gave us – we were a young team – I think he was probably the biggest catalyst of the game in this country.

Gansler: I was never disappointed [about being fired]. I was more bothered that when we finally got the MLS I wasn’t one of the first eight coaches to get his own team.

7. The shot heard round the world part II

Stollmeyer: There was a reunion game in Trinidad.

Krumpe: I think it was 2009 – 20 years after.

Stollmeyer: I remember it being 17 years after, so 2007?

Windischmann: I started getting a couple of phone calls. At Thanksgiving time they were looking to take some guys over to Trinidad to play a reunion game. One of the guys I see from the Trinidad team I see in the US. I saw him in a Dunkin’ Donuts – I was getting coffee with my wife. He waves: “Hey! How you doing?” And he’s talking about the game.

Trittschuh: Desmond Armstrong put it together. He had called and said: “Would you be interested in this?” Then he called one time and said it was off. Then two or three weeks before the game he said: “It’s on. Are you going?”

Krumpe: I got a phone call two weeks ahead of time: “Can you play?”

Windischmann: It started to get shady. You pay for the ticket and we give you the money back. You’re worried already. Then they were going to give us $1,200 after the game. I was willing to go anyway.

Krumpe: We kind of showed up and said: “Hey, OK, we’re here.”

Windischmann: We went there and went to the stadium where we played. Trinidad was training they were all ready for us. Those guys had been playing for a month and a month-and-a-half, exhibition games – everything – they were ready for revenge.

Stollmeyer: We only had nine guys, and they were going to get some guys from the embassy to play. We said: “We aren’t playing like that.” So they got us some guys.

Trittschuh: I wish more guys had gone.

Stollmeyer: Different guys’ flights were messed up. There were a couple guys coming from San Jose, California, but the tickets that were sent to them were from San Juan, Puerto Rico.

Windischmann: Robin Fraser [US national team player in the 1980s who was not on World Cup team] came down.

Stollmeyer: Two minutes into the game Caligiuri scores.

Windischmann: It was so ironic. The whistle blows and a couple minutes after I send a free kick over. Caligiuri controls it and scores the first goal. The whole stadium got quiet. What the hell just happened? Trinidad all over again. Then after that Trinidad started scoring some goals.

Stollmeyer: They ended up winning 3-1. We were completely exhausted.

Windischmann: I had torn my ACL, and got it fixed, and then had torn it again, and never got it fixed. I played the whole game with that torn ACL They told us we got only 12 guys. What? So I wound up playing almost the whole game. I couldn’t bend my knee after that!

Krumpe: They had promised to pay us, and without a crowd they had no money. But it was not about the money. For me it was about the chance to get back together with the guys.

For the original article with photos and video, click here.

Goalkeeper –

Goalkeeper –

Dr. Joe Machnik is the Founder of No. 1 Soccer Camps, FIFA/CONCACAF Match Commissioner, and a

Dr. Joe Machnik is the Founder of No. 1 Soccer Camps, FIFA/CONCACAF Match Commissioner, and a

88-54-6, including an Allegheny Mountain Collegiate Conference (AMCC) record of 49-22-2. The Panthers team qualified for seven straight conference postseasons including four straight runner-up seasons. During that time the Panthers have dominated the AMCC awards with numerous All-Conference honors in addition to Offensive and Defensive Player of the Year awards. In addition, Idland was first named the AMCC Coach of the year in 2011 after leading Pitt-Bradford to an impressive 13-3-2 record. He also was awarded the AMCC Co-Coach of the year this past season. Idland’s 2014 team set a new school record after a 15-5-0 year, which also resulted in the program’s first ever regular season championship.

88-54-6, including an Allegheny Mountain Collegiate Conference (AMCC) record of 49-22-2. The Panthers team qualified for seven straight conference postseasons including four straight runner-up seasons. During that time the Panthers have dominated the AMCC awards with numerous All-Conference honors in addition to Offensive and Defensive Player of the Year awards. In addition, Idland was first named the AMCC Coach of the year in 2011 after leading Pitt-Bradford to an impressive 13-3-2 record. He also was awarded the AMCC Co-Coach of the year this past season. Idland’s 2014 team set a new school record after a 15-5-0 year, which also resulted in the program’s first ever regular season championship.

No. 1 Regional Director Graeme Orr has been with No.1 Soccer Camps since 2003. In addition, he is also the

No. 1 Regional Director Graeme Orr has been with No.1 Soccer Camps since 2003. In addition, he is also the

No.1 Soccer Camp is pleased to announce our new location at Wayland Academy in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. The facilities and location of our new site are stellar – less than an 90-minutedrive from Madison, Milwaukee, Appleton or Rockford, Illinois.

No.1 Soccer Camp is pleased to announce our new location at Wayland Academy in Beaver Dam, Wisconsin. The facilities and location of our new site are stellar – less than an 90-minutedrive from Madison, Milwaukee, Appleton or Rockford, Illinois. rich tradition with modern amenities.The facilities are superb across the board. No. 1 campers willtrain on the immaculate soccer fields, have use of the pool, and access to the iconic Wayland Field House – a truly one of a kind facility. The dormitories are comfortable and close to the fields and dining facility – a key factor as legs tired during the week! The food at Wayland Academy is exceptional and abundant offering a variety of choices for every appetite. The combination of No. 1 Soccer Camps’ exceptional training, Wayland Academy’s state of the art facilities and our German coaches and campers joining us is going to make for a fantastic week of soccer!

rich tradition with modern amenities.The facilities are superb across the board. No. 1 campers willtrain on the immaculate soccer fields, have use of the pool, and access to the iconic Wayland Field House – a truly one of a kind facility. The dormitories are comfortable and close to the fields and dining facility – a key factor as legs tired during the week! The food at Wayland Academy is exceptional and abundant offering a variety of choices for every appetite. The combination of No. 1 Soccer Camps’ exceptional training, Wayland Academy’s state of the art facilities and our German coaches and campers joining us is going to make for a fantastic week of soccer!

they ventured into the Rain Forest for a team rafting trip down the Sarapiqui River. Day six started with a trip to the Robleato Children’s Center for community service. For players and coaches alike, it was a humbling, but incredibly rewarding experience. While there, the team the players and staff socialized and played with the children. Although children spoke English, the Americans found common ground with a soccer ball at their feet, swings, monkey bars, and other playground equipment. The highlight – and tear jerker – was the 5 year old boy who blessed the team for coming to spend the day to play with them.

they ventured into the Rain Forest for a team rafting trip down the Sarapiqui River. Day six started with a trip to the Robleato Children’s Center for community service. For players and coaches alike, it was a humbling, but incredibly rewarding experience. While there, the team the players and staff socialized and played with the children. Although children spoke English, the Americans found common ground with a soccer ball at their feet, swings, monkey bars, and other playground equipment. The highlight – and tear jerker – was the 5 year old boy who blessed the team for coming to spend the day to play with them. Inspired by the visit, the team quickly turned it around in preparation for Game Three versus UCEM Alajuela. The team wasted no time with goals at 1:08, 8:47, 22:53, and 25:46 to move onto an impressive 4-0 win. “The game plan was to jump on them right away and score early and often given the referees no decisions in the game,” said Gregg. “We knew if we could get on them fast , we could then control the tempo and get them off their game plan.”

Inspired by the visit, the team quickly turned it around in preparation for Game Three versus UCEM Alajuela. The team wasted no time with goals at 1:08, 8:47, 22:53, and 25:46 to move onto an impressive 4-0 win. “The game plan was to jump on them right away and score early and often given the referees no decisions in the game,” said Gregg. “We knew if we could get on them fast , we could then control the tempo and get them off their game plan.” No. 1 Regional Director John Gregg first came to

No. 1 Regional Director John Gregg first came to

No. 1 Regional Director Christine Huber has been with

No. 1 Regional Director Christine Huber has been with

Jones, who was UU’s co-captain and field general on the pitch this season, started 19 matches in goal for the Blue Knights. The 2015 All-MEC first teamer finished second in the conference in goals against average (0.81), save percentage (.803), and ranked fifth in total saves (61).

Jones, who was UU’s co-captain and field general on the pitch this season, started 19 matches in goal for the Blue Knights. The 2015 All-MEC first teamer finished second in the conference in goals against average (0.81), save percentage (.803), and ranked fifth in total saves (61). announced by the organization.

announced by the organization.

rostered, won it’s 4th consecutive NSCAA Ethics Award this season. Given annually, the award recognizes teams that exhibit fair play, sporting behavior and adherence to the laws of the game. This is reflected by the number of yellow caution cards or red ejection cards they are shown by referees throughout the season based on the number of cards accumulated divided by the number of games played.

rostered, won it’s 4th consecutive NSCAA Ethics Award this season. Given annually, the award recognizes teams that exhibit fair play, sporting behavior and adherence to the laws of the game. This is reflected by the number of yellow caution cards or red ejection cards they are shown by referees throughout the season based on the number of cards accumulated divided by the number of games played.

“The No.1 Soccer Camps have stood the test of time due to the guidance and leadership of Dr. Joseph Machnik,” said No. 1 Soccer Camps Regional Director Greg Andrulis. “From the beginning, the camp has been dedicated to providing the most advanced and compelling experience for the staff and players in attendance. Many of the country’s and the world top players and coaches have become part of the camp’s legacy. Always striving to be No.1, the search for excellence continues today. It’s a true testament to Dr. Joe that many of his current staff have been part of this experience for well over 20 years, and a few from the beginning. It’s amazing to think how many players and coaches have benefitted from the lessons and teachings of Dr. Joe. He is a true icon in the American soccer culture and his contributions are immeasurable.”

“The No.1 Soccer Camps have stood the test of time due to the guidance and leadership of Dr. Joseph Machnik,” said No. 1 Soccer Camps Regional Director Greg Andrulis. “From the beginning, the camp has been dedicated to providing the most advanced and compelling experience for the staff and players in attendance. Many of the country’s and the world top players and coaches have become part of the camp’s legacy. Always striving to be No.1, the search for excellence continues today. It’s a true testament to Dr. Joe that many of his current staff have been part of this experience for well over 20 years, and a few from the beginning. It’s amazing to think how many players and coaches have benefitted from the lessons and teachings of Dr. Joe. He is a true icon in the American soccer culture and his contributions are immeasurable.” professional players and international stars, and we think about the nearly 100,000 participants, campers and staff and those that have excelled at the highest levels of our sport. But most of all, we remember the sheer joy on campers faces, the huge smiles when learning takes place and the level of satisfaction achieved in so many ways. It certainly has been a great run, and with the renewed vigor and leadership of our current Directors and Staff, No.1 Soccer Camps will continue to be on the cutting edge in providing the absolute best in soccer camp experience. No. 1 For A Reason!”

professional players and international stars, and we think about the nearly 100,000 participants, campers and staff and those that have excelled at the highest levels of our sport. But most of all, we remember the sheer joy on campers faces, the huge smiles when learning takes place and the level of satisfaction achieved in so many ways. It certainly has been a great run, and with the renewed vigor and leadership of our current Directors and Staff, No.1 Soccer Camps will continue to be on the cutting edge in providing the absolute best in soccer camp experience. No. 1 For A Reason!”

officially open for the 2016 season. As a little incentive to get the ball rolling, we’re offering a limited time Early Bird offer so you can SAVE up to $50.00 off your 2016 program fees!

officially open for the 2016 season. As a little incentive to get the ball rolling, we’re offering a limited time Early Bird offer so you can SAVE up to $50.00 off your 2016 program fees!

Campers will be initially placed into groups based on the program that they have enrolled during registration. During the sessions on the first day, campers will evaluated on their ability, throughout the week there will be continued evaluation as the program progresses.

Campers will be initially placed into groups based on the program that they have enrolled during registration. During the sessions on the first day, campers will evaluated on their ability, throughout the week there will be continued evaluation as the program progresses.

– Day Camp, Federalsburg, MD – Day Camp shown on left) recently produced a new podcast for SoccerOffice.com that gives listeners an inside look at No. 1 Soccer Camps.

– Day Camp, Federalsburg, MD – Day Camp shown on left) recently produced a new podcast for SoccerOffice.com that gives listeners an inside look at No. 1 Soccer Camps.

Adam Manning is the Regional Director at No. 1 Soccer Camps at Salisbury University – Day Camp and Federalsburg, MD – Day Camp. Adam recently stepped down as DOC of CCYSA to launch Soccer Office and Soccer Office Media, the first soccer specific podcasting company that focuses on storytelling and documentaries.

Adam Manning is the Regional Director at No. 1 Soccer Camps at Salisbury University – Day Camp and Federalsburg, MD – Day Camp. Adam recently stepped down as DOC of CCYSA to launch Soccer Office and Soccer Office Media, the first soccer specific podcasting company that focuses on storytelling and documentaries.

long tradition in the soccer community. Each summer we have former campers returning to bring their children to camp and campers who have gone onto play at the collegiate and professional level are returning to coach. Shown to the left is the McLaughlin family. Dad Ryan, a No. 1 veteran, brought his son Connor and daughter Callie to the No. 1 Soccer Camps in Salisbury Maryland recently. Players who attend our camps become a member of an incredible fraternity and lifelong members of the No.1 Soccer Camps family. We hope to see you and your sons this summer!

long tradition in the soccer community. Each summer we have former campers returning to bring their children to camp and campers who have gone onto play at the collegiate and professional level are returning to coach. Shown to the left is the McLaughlin family. Dad Ryan, a No. 1 veteran, brought his son Connor and daughter Callie to the No. 1 Soccer Camps in Salisbury Maryland recently. Players who attend our camps become a member of an incredible fraternity and lifelong members of the No.1 Soccer Camps family. We hope to see you and your sons this summer!

there looks like it’s about to start. I’ll be quick!

there looks like it’s about to start. I’ll be quick! John Adams is No. 1 Soccer Camps Associate Director. A long time No.1 staff member, Coach John has served as Goalkeeper Director and Striker Director throughout the years. He is also currently the Associate Head Coach and Goalkeeper Coach for Women’s Soccer at Albert Magnus College, where in 2013, his team reached the ECAC Finals. Adams will be directing and coaching at

John Adams is No. 1 Soccer Camps Associate Director. A long time No.1 staff member, Coach John has served as Goalkeeper Director and Striker Director throughout the years. He is also currently the Associate Head Coach and Goalkeeper Coach for Women’s Soccer at Albert Magnus College, where in 2013, his team reached the ECAC Finals. Adams will be directing and coaching at

Campers will be initially placed into groups based on the program that they have enrolled during registration. During the sessions on the first day, campers will evaluated on their ability, throughout the week there will be continued evaluation as the program progresses.

Campers will be initially placed into groups based on the program that they have enrolled during registration. During the sessions on the first day, campers will evaluated on their ability, throughout the week there will be continued evaluation as the program progresses.

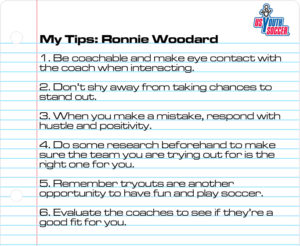

the player is coachable and exhibits a lot of effort, which can be displayed in a multitude of ways. “One of the little tricks in tryouts is to always keep eye contact with the coaches during drills and when the coach is giving you their input. You also should try to implement these points immediately,” Woodard said. “A player’s work rate on and off the ball are equally as important.”

the player is coachable and exhibits a lot of effort, which can be displayed in a multitude of ways. “One of the little tricks in tryouts is to always keep eye contact with the coaches during drills and when the coach is giving you their input. You also should try to implement these points immediately,” Woodard said. “A player’s work rate on and off the ball are equally as important.”

ball. In almost every instance, the second video shows a dramatic improvement in technique. The secret to the success? During the course of this session, players perform hundreds of repetitions to instill the ability to feel comfortable when put in goal scoring opportunities. This training session helps young soccer players gain confidence in their ability to correctly strike a ball and put it on target – this repetition and persistence allows them to turn their failures into extraordinary goals.

ball. In almost every instance, the second video shows a dramatic improvement in technique. The secret to the success? During the course of this session, players perform hundreds of repetitions to instill the ability to feel comfortable when put in goal scoring opportunities. This training session helps young soccer players gain confidence in their ability to correctly strike a ball and put it on target – this repetition and persistence allows them to turn their failures into extraordinary goals. Rob Andrulis is an Associate Director for No. 1 Soccer Camps. In addition, he is also the Head Coach of Boys Soccer at Litchfield High School. Coach Rob will be at the following No. 1 locations camps this summer:

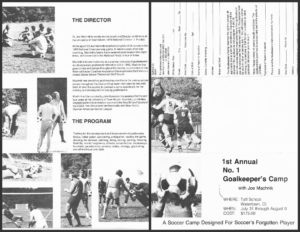

Rob Andrulis is an Associate Director for No. 1 Soccer Camps. In addition, he is also the Head Coach of Boys Soccer at Litchfield High School. Coach Rob will be at the following No. 1 locations camps this summer:  In 1977, three years after receiving one of the country’s first “A” coaching licenses, Joe Machnik, then a coach at the University of New Haven, started the first nationally recognized camp for goalkeepers, No.1 Goalkeeper Camp. In a few short years, No.1 grew to be the “in” place for goalkeepers, and the staff was a virtual “Who’s Who” among American and foreign goalkeepers playing in both the Pro’s and collegiate soccer realms.During this time, it was not unusual at that time to see a camp of 150 – 250 goalkeepers at a single No.1 location. Within 10 years, however, Machnik and partner John Kowalski, came to the realization that the technical training, the how to perform a certain skill or technique, was not enough to advance the American goalkeeper. There was a need for more traditional training to answer the questions of “when, where and why” as that training could only be done in the presence of field players playing in match like situations. Hence, the founding of the Star Striker School, which became the fore-runner of the No.1 Striker Camp and an important component of the No.1 Soccer Camps program.By the middle 1990’s, after the World Cup of 1994 played in America and the winning of the Women’s World Cup and Gold Medal in Olympic Women’s Soccer, youth soccer became increasingly mainstream and millions of American boys AND girls now played the game. While camps were still important at that time – and were centers of fine teaching and coaching – the club system began to take hold in the US, and players could receive good coaching at the club, high school and college level. By 2000, most established players were being identified early by the club system, and many camps ceased operation as the summer soccer camp was no longer the only place to receive fine coaching and a chance to play some real soccer.

In 1977, three years after receiving one of the country’s first “A” coaching licenses, Joe Machnik, then a coach at the University of New Haven, started the first nationally recognized camp for goalkeepers, No.1 Goalkeeper Camp. In a few short years, No.1 grew to be the “in” place for goalkeepers, and the staff was a virtual “Who’s Who” among American and foreign goalkeepers playing in both the Pro’s and collegiate soccer realms.During this time, it was not unusual at that time to see a camp of 150 – 250 goalkeepers at a single No.1 location. Within 10 years, however, Machnik and partner John Kowalski, came to the realization that the technical training, the how to perform a certain skill or technique, was not enough to advance the American goalkeeper. There was a need for more traditional training to answer the questions of “when, where and why” as that training could only be done in the presence of field players playing in match like situations. Hence, the founding of the Star Striker School, which became the fore-runner of the No.1 Striker Camp and an important component of the No.1 Soccer Camps program.By the middle 1990’s, after the World Cup of 1994 played in America and the winning of the Women’s World Cup and Gold Medal in Olympic Women’s Soccer, youth soccer became increasingly mainstream and millions of American boys AND girls now played the game. While camps were still important at that time – and were centers of fine teaching and coaching – the club system began to take hold in the US, and players could receive good coaching at the club, high school and college level. By 2000, most established players were being identified early by the club system, and many camps ceased operation as the summer soccer camp was no longer the only place to receive fine coaching and a chance to play some real soccer. camper does not have to be the best player in order to attend. Campers are organized in mobile groups, first by age, size, and ability with adjustments to the group structure and makeup being made each day as the week progresses. More importantly, campers develop an appreciation for the soccer’s inner values as the intrinsic rewards of participation and success are constantly stressed. At week’s end, a thorough 75 point evaluation form is presented to each camper with a personal development plan citing areas to be worked on during and after the season. Machnik credits the evaluation form as a critical factor in the decision parents make to return their campers to No.1 year after year.

camper does not have to be the best player in order to attend. Campers are organized in mobile groups, first by age, size, and ability with adjustments to the group structure and makeup being made each day as the week progresses. More importantly, campers develop an appreciation for the soccer’s inner values as the intrinsic rewards of participation and success are constantly stressed. At week’s end, a thorough 75 point evaluation form is presented to each camper with a personal development plan citing areas to be worked on during and after the season. Machnik credits the evaluation form as a critical factor in the decision parents make to return their campers to No.1 year after year.

Camp promotes community. It creates this great space that shows kids how to live together and care for one another. There are norms and negotiation of boundaries; there are rules. Camp is a place where kids can “practice” growing up stretching their social, emotional, physical, and cognitive muscles outside the context of their immediate family. This is what childhood is supposed to provide.

Camp promotes community. It creates this great space that shows kids how to live together and care for one another. There are norms and negotiation of boundaries; there are rules. Camp is a place where kids can “practice” growing up stretching their social, emotional, physical, and cognitive muscles outside the context of their immediate family. This is what childhood is supposed to provide.

one 2015 session of No. 1 Soccer Camp. The winning bid amount will be donated to the

one 2015 session of No. 1 Soccer Camp. The winning bid amount will be donated to the

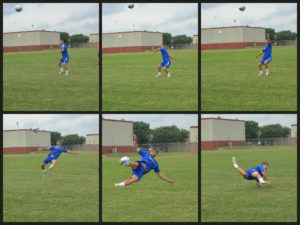

ground. We stress the importance of body control, core strength, mental focus and making clean contact on the ball. Players then move to their feet to hone their perception, coordination and footwork while adjusting to the flight of the ball. Finally, we teach our campers how to land safely, using their upper body and arms to cushion their landing. Of course, at the end of each lesson the campers always have the chance to then apply what they have learned in a live small-sided game.

ground. We stress the importance of body control, core strength, mental focus and making clean contact on the ball. Players then move to their feet to hone their perception, coordination and footwork while adjusting to the flight of the ball. Finally, we teach our campers how to land safely, using their upper body and arms to cushion their landing. Of course, at the end of each lesson the campers always have the chance to then apply what they have learned in a live small-sided game. Nicholas DeMarsh is the No. 1 Soccer Camps Striker Director at our West Conn site. In addition, he just concluded his 13th year as the head coach of Buffalo State’s women’s soccer program in 2014, leading the Bengals to the SUNYAC semifinals for the second season in a row. DeMarsh, the 2010 SUNYAC Coach of the Year, has guided the Bengals to winning seasons in seven of the past 11 seasons and has a career record of 102-108-32.

Nicholas DeMarsh is the No. 1 Soccer Camps Striker Director at our West Conn site. In addition, he just concluded his 13th year as the head coach of Buffalo State’s women’s soccer program in 2014, leading the Bengals to the SUNYAC semifinals for the second season in a row. DeMarsh, the 2010 SUNYAC Coach of the Year, has guided the Bengals to winning seasons in seven of the past 11 seasons and has a career record of 102-108-32.

different each year?

different each year? The coaches at No.1 are definitely top notch coaches – in my opinion they are among some of the best in the country. The training sessions at camp were very good, and I felt like I was being challenged every session. The Camp Directors

The coaches at No.1 are definitely top notch coaches – in my opinion they are among some of the best in the country. The training sessions at camp were very good, and I felt like I was being challenged every session. The Camp Directors  Women’s College Cup for Florida State to give them their first Soccer National Championship. Can you describe that moment and feeling?

Women’s College Cup for Florida State to give them their first Soccer National Championship. Can you describe that moment and feeling?

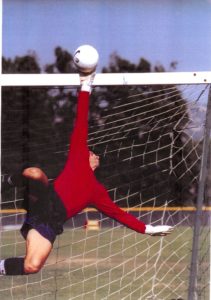

goalkeeper’s demeanor during training. The training ground is where the goalkeeper becomes hard or soft; it is where the goalkeeper works out problems and imprints habits; and it is where the goalkeeper has the most candid and unrestricted exchange with the coach and other goalkeepers. Ideally, the majority of this attitude toward training is learned holistically through example – almost as if by osmosis. Top end goalkeeper camps like

goalkeeper’s demeanor during training. The training ground is where the goalkeeper becomes hard or soft; it is where the goalkeeper works out problems and imprints habits; and it is where the goalkeeper has the most candid and unrestricted exchange with the coach and other goalkeepers. Ideally, the majority of this attitude toward training is learned holistically through example – almost as if by osmosis. Top end goalkeeper camps like  Work hard, but relax. Often, when a young goalkeeper first “catches the bug” and wraps her head around a training ethic, she will over do it. That is to say that she might work so hard that she becomes frantic and her performance suffers as a result. There is nothing good about a frantic goalkeeper. But, refining this youngster’s approach is not very difficult and it is fun to do! The young player must learn to recognize the difference between a controlled high work rate and going crazy. This is one of the elements of the goalkeeper’s training mentality that can be coached directly. Again, the best way is by means of example. A young, accomplished staff coach’s (or perhaps an older, more experienced player’s) demonstration paints the best picture here. Put him in a training exercise and let him go to work. As he is playing, point out to the young goalkeeper how controlled his movement is. He is always focused. His feet, for example, are always precise in their movement and set at the right times. Yet, he is always pushing the pace at which the training moves: making saves and bouncing right back up for more; returning balls accurately and swiftly to the server; playing just a bit faster than the serve so as to ask the server to test him more on the next one. These traits are the embodiment of the very valuable lesson to work hard, but relax.

Work hard, but relax. Often, when a young goalkeeper first “catches the bug” and wraps her head around a training ethic, she will over do it. That is to say that she might work so hard that she becomes frantic and her performance suffers as a result. There is nothing good about a frantic goalkeeper. But, refining this youngster’s approach is not very difficult and it is fun to do! The young player must learn to recognize the difference between a controlled high work rate and going crazy. This is one of the elements of the goalkeeper’s training mentality that can be coached directly. Again, the best way is by means of example. A young, accomplished staff coach’s (or perhaps an older, more experienced player’s) demonstration paints the best picture here. Put him in a training exercise and let him go to work. As he is playing, point out to the young goalkeeper how controlled his movement is. He is always focused. His feet, for example, are always precise in their movement and set at the right times. Yet, he is always pushing the pace at which the training moves: making saves and bouncing right back up for more; returning balls accurately and swiftly to the server; playing just a bit faster than the serve so as to ask the server to test him more on the next one. These traits are the embodiment of the very valuable lesson to work hard, but relax. Mike Idland

Mike Idland

Mike Idland tackles mistake management and troubleshooting common reactions to technical and tactical mistakes by goalkeepers.

Mike Idland tackles mistake management and troubleshooting common reactions to technical and tactical mistakes by goalkeepers. Another very simple adage I use over and over again with my goalkeepers is Always the next ball. If during the periods between action, the keeper’s frame of mind and focus is always on the next ball, then she will give herself the best chance possible to perform to her full ability at all times. This must be the approach whether she has just made the biggest blunder of her career or the greatest save of her life: Always the next ball. The maturity that this requires does not usually come to goalkeepers on its own until they are quite old and the development of humility, as a natural piece of their personalities, comes to be. But, it can be taught at a relatively young age under the following conditions: the goalkeeper has an open mind; the goalkeeper coach knows and understands the goalkeeper as a person; the goalkeeper coach knows and understands the type of goalkeeper with whom he is working; and the keeper trusts her coach (and her team). Before going into more depth on types of goalkeepers and mistake management, it is worth stating something I think everyone in the goalkeeper’s sphere (the team, the coach, the fans, and the keeper herself) will agree on after a mistake: everyone wants to get the next play right, so everyone will be happy if the goalkeeper is able to is able to bounce right back into the game and get the next ball! Big time goalkeepers such as the professionals and internationals mentioned before understand this, and this is what keeps them playing at a high level even after they let up a howler.

Another very simple adage I use over and over again with my goalkeepers is Always the next ball. If during the periods between action, the keeper’s frame of mind and focus is always on the next ball, then she will give herself the best chance possible to perform to her full ability at all times. This must be the approach whether she has just made the biggest blunder of her career or the greatest save of her life: Always the next ball. The maturity that this requires does not usually come to goalkeepers on its own until they are quite old and the development of humility, as a natural piece of their personalities, comes to be. But, it can be taught at a relatively young age under the following conditions: the goalkeeper has an open mind; the goalkeeper coach knows and understands the goalkeeper as a person; the goalkeeper coach knows and understands the type of goalkeeper with whom he is working; and the keeper trusts her coach (and her team). Before going into more depth on types of goalkeepers and mistake management, it is worth stating something I think everyone in the goalkeeper’s sphere (the team, the coach, the fans, and the keeper herself) will agree on after a mistake: everyone wants to get the next play right, so everyone will be happy if the goalkeeper is able to is able to bounce right back into the game and get the next ball! Big time goalkeepers such as the professionals and internationals mentioned before understand this, and this is what keeps them playing at a high level even after they let up a howler. highly-technical goalkeeper “giving up” in the middle of an awkward situation such as a scramble in front of the goal. It is easy for the coach to jump to the assumption that the keeper doesn’t care because of her actions, and that is an understandable reaction. But, this scenario is usually a bit deeper than that and understanding the inner workings of this problem for the goalkeeper will go a long way in helping her and, consequently, helping your team in the long run.

highly-technical goalkeeper “giving up” in the middle of an awkward situation such as a scramble in front of the goal. It is easy for the coach to jump to the assumption that the keeper doesn’t care because of her actions, and that is an understandable reaction. But, this scenario is usually a bit deeper than that and understanding the inner workings of this problem for the goalkeeper will go a long way in helping her and, consequently, helping your team in the long run.

mentality,” and this would not be incorrect. But, the goalkeeper’s approach, her focus, extends so far beyond training that the term “training” seems to limit the psyche unjustly. In a sense, the goalkeeper almost has a governing philosophy or a world view. We can say of many great goalkeepers – whether at the youth or senior levels – that “she carries herself like a goalkeeper,” or, “you can just tell she is a goalkeeper.” Why is that? Why is it that the good ones act like goalkeepers even when they are not practicing their craft on the field of play?

mentality,” and this would not be incorrect. But, the goalkeeper’s approach, her focus, extends so far beyond training that the term “training” seems to limit the psyche unjustly. In a sense, the goalkeeper almost has a governing philosophy or a world view. We can say of many great goalkeepers – whether at the youth or senior levels – that “she carries herself like a goalkeeper,” or, “you can just tell she is a goalkeeper.” Why is that? Why is it that the good ones act like goalkeepers even when they are not practicing their craft on the field of play?

The thing is that the goalkeeper rarely does anything without the attention of the team and coach on her. So, if she is to succeed in the context of the team, she must wear her heart on her sleeve and handle any of the above situations and the countless others that may arise with the utmost poise. When the team trusts the goalkeeper (and there must be trust between the goalkeeper and the team if there is to be success), they will often model their own demeanor after how the goalkeeper reacts to key moments. That is to say, if the goalkeeper is confident and composed at a critical moment, then the team is likely to be confident and composed. If the goalkeeper is panicked and defeated at this moment, then the team may lose heart. For some goalkeepers, the feeling is that this is an unfair element to goalkeeping; they would rather just go about their business quietly, blending in, with no more or no less responsibility than any other player on the team. But, the thing is the goalkeeper occupies a position that is different from the other players. And with this position comes what has elsewhere been termed the burden of responsibility. In other words, like it or not, the goalkeeper will be looked to as an example by the team and the coach.

The thing is that the goalkeeper rarely does anything without the attention of the team and coach on her. So, if she is to succeed in the context of the team, she must wear her heart on her sleeve and handle any of the above situations and the countless others that may arise with the utmost poise. When the team trusts the goalkeeper (and there must be trust between the goalkeeper and the team if there is to be success), they will often model their own demeanor after how the goalkeeper reacts to key moments. That is to say, if the goalkeeper is confident and composed at a critical moment, then the team is likely to be confident and composed. If the goalkeeper is panicked and defeated at this moment, then the team may lose heart. For some goalkeepers, the feeling is that this is an unfair element to goalkeeping; they would rather just go about their business quietly, blending in, with no more or no less responsibility than any other player on the team. But, the thing is the goalkeeper occupies a position that is different from the other players. And with this position comes what has elsewhere been termed the burden of responsibility. In other words, like it or not, the goalkeeper will be looked to as an example by the team and the coach.

Soubrier was recruited to

Soubrier was recruited to  the benefits of Soubrier’s on and off the pitch talentsin 2014. From running sunrise PT sessions, to demoing drills to making sure each camper was properly cared for, Soubrier found a perfect professional fit with No. 1 Soccer Camps.

the benefits of Soubrier’s on and off the pitch talentsin 2014. From running sunrise PT sessions, to demoing drills to making sure each camper was properly cared for, Soubrier found a perfect professional fit with No. 1 Soccer Camps.

thinking about the outcome and dwelling on the consequences. A fear of failure may creep in and affect the performance in the must score situation. This effect is prominent regardless of a player’s status, but has an incredibly negative effect on players of elite status. Examples are plentiful – Maradona, Platini, van Basten, Roberto Baggio all were soccer legends who got it wrong when it mattered the most.

thinking about the outcome and dwelling on the consequences. A fear of failure may creep in and affect the performance in the must score situation. This effect is prominent regardless of a player’s status, but has an incredibly negative effect on players of elite status. Examples are plentiful – Maradona, Platini, van Basten, Roberto Baggio all were soccer legends who got it wrong when it mattered the most.

Camp in Urbana again this year. To use their words, they had an “amazing” time. Each year, I hear stories for days about their good times on and off the field. This year was even more special because of the World Cup games they viewed with the entire camp. The boys always agree that the competition level, and the soccer instruction are the most intense at No.1. Needless to say, knowing Marc and Max, they love it! I appreciate knowing they are fine with you and your staff and having the opportunity to hear their stories each year. This was their third year in attendance, and I am sure they will be back for more! Thanks again!” – Susan, No. 1 Soccer Camps at Urbana Parent

Camp in Urbana again this year. To use their words, they had an “amazing” time. Each year, I hear stories for days about their good times on and off the field. This year was even more special because of the World Cup games they viewed with the entire camp. The boys always agree that the competition level, and the soccer instruction are the most intense at No.1. Needless to say, knowing Marc and Max, they love it! I appreciate knowing they are fine with you and your staff and having the opportunity to hear their stories each year. This was their third year in attendance, and I am sure they will be back for more! Thanks again!” – Susan, No. 1 Soccer Camps at Urbana Parent  “I just wanted to share with you that Melanie thought this was the best soccer camp she’s ever attended. She said that she got so much more out of it than the ODP Developmental camp in May, so you and the coaching staff should feel especially proud! The player evaluation form was much more detailed and individualized as compared to the ODP form. Melanie has been given more specific insights on how to improve her performance this season and beyond. The only thing she could think of to make it better would be more camps in Vero throughout the year to hone her skills. Looking forward to the next camp.” – Cindy, No. 1 Soccer Camps at Vero Beach Parent